When I first looked at Vue vs React, I chose VueJS. One of the reasons was that I felt like Vue was a better choice was the complexity of React classes and life-cycle events. I felt like that was a lot of extra complication that would help with developing frameworks, but preferred the simplicity of Vue’s HTML-like templates and Angular-like two-way data-bindings.

As working with Gutenberg has caused me to readdress React, I’ve found that React can, in many ways be a lot simpler, because I can stick to small, pure functions for most of my components.

One thing I love about React is how easy it is to test and refactor when you follow the single responsibility of concerns principle. This series of post is on a meta-level about avoiding coupling and cohesion when writing code. I’m using React components as a practical example, so you learn React. My friend Carl wrote a really great post about how cohesion and strong coupling happen in WordPress PHP projects and beyond.

Becoming Test-Driven

In my previous posts in this series, I went over React basics. In the rest of this series, I’m going to cover using React with WordPress, starting with the WordPress REST API and then React. I’ll be walking through creating a small application that displays and edits posts from the WordPress REST API. I’m not actually going to connect it to the WordPress REST API. This is important. I used to start by getting my API requests working and then write JavaScript to display it. This is completely backward in my mind and prevents decoupling the WordPress front-end from the server.

By starting with test data, I am forced to develop code with near or complete code coverage. I also think it’s much faster than cowboy coding against a live API and having to refresh a browser all the time. The phase of front-end development I’m teaching here — creating HTML with JavaScript as opposed to confirming that HTML to a design — does not require a web browser.

Yes, end to end testing with a headless browser may be useful, though I do not use it. But my point is that relying on what the browser looks like is not only a poor test. Using tests instead of the browser forces a pattern of development that I find to be faster and more maintainable.

By developing in this fashion, I have increased my output of code significantly and I have a lot more confidence in what I am writing. Also, knowing that I have to live with this code long-term, it’s important to me to have Coveralls and Code Climate in place to enforce these standards and measure improvement over time.

ES6 Classes

If you started in PHP, like I did, which is not an object-oriented language by default, you may conflate classes with object-oriented programming. This is a false distinction. For example, in JavaScript, we can treat primitive data types — strings, integers, arrays — etc. as objects and even extend their functionality by modifying their prototype.

This is Prototypal Inheritance, which is different from how we extend classes, via classical inheritance, in PHP by overriding methods.

JavaScript does not have “methods” in the form that class-based languages define them. In JavaScript, any function can be added to an object in the form of a property. An inherited function acts just as any other property, including property shadowing as shown above (in this case, a form of method overriding).

Personally, I find Prototypal Inheritance a lot harder to understand than classical inheritance. EcmaScript 6 introduced classes into JavaScript as syntactic sugar.

In computer science, syntactic sugar is syntax within a programming language that is designed to make things easier to read or to express. It makes the language “sweeter” for human use: things can be expressed more clearly, more concisely, or in an alternative style that some may prefer.

Wikipedia, Emphasis mine.

I was super-geeked when classes became available in JavaScript, but having spent more time with them, especially developing React components, I feel like they should be used sparingly.

Pure Functions And Testability

I’m not arguing that you should never extend React.Component, it’s useful, but I always default to small, functional components. Why? They are pure functions — arguments go in, output comes out, no side effects. Pure functions are easy to test. They do not have side effects by default, which is a condition for true unit testing.

Here is a function, which is not pure, that modifies the title of a post in a collection:

View the code on Gist.

I say this is not pure as it modifies the variable post, which is not in the scope it includes. Therefore, the modification of the posts variable is a side-effect of this function. If I was to write a test for this function, I’d have to mock the global, which is fine, but does that prove anything, given that the test covers elements outside of its control? Sort of.

Let’s refactor to a pure function that is testable. We need to modify an array of posts. By injecting that array into the function, we go from modifying an array of posts to modifying the passed array of post.

View the code on Gist.

I just applied the principle of dependency injection so that the function can be isolated.

In software engineering, dependency injection is a technique whereby one object (or static method) supplies the dependencies of another object. A dependency is an object that can be used (a service). An injection is the passing of a dependency to a dependent object (a client) that would use it.

One key benefit of dependency injection is that we can inject mock data when testing. Instead of mocking a global and hoping that’s accurate, we are testing the function exactly the way it actually is used.

View the code on Gist.

Yes, we can test class methods as well. I’ll get to that, but it’s more complicated. I’ll get to when that complication is worth it, but let’s look at when its not first.

A Quick Intro To Unit Testing React Components With Jest

While there are a lot of options for testing JavaScript apps, Jest, is built by Facebook with React in mind. Even if you’ve never written JavaScript tests before, I think it’s worth learning testing right away. If you know how to write a JavaScript function, you can write a test with Jest.

Let’s walk through setting up tests and writing your first tests. As this post goes on, we’ll add more features to the example app, using tests to guide the development. This will allow us to start small, and build complexity one layer at a time, with our tests making sure nothing falls apart in the process.

Getting Tests Running

First, let’s create a new React app, with a dev server, and everything we need to run tests. Coming from a WordPress background, that sounds hard, but like a developer-friendly framework should, this is easy with React. Seriously, its three commands if you have Node, npm and yarn installed.

View the code on Gist.

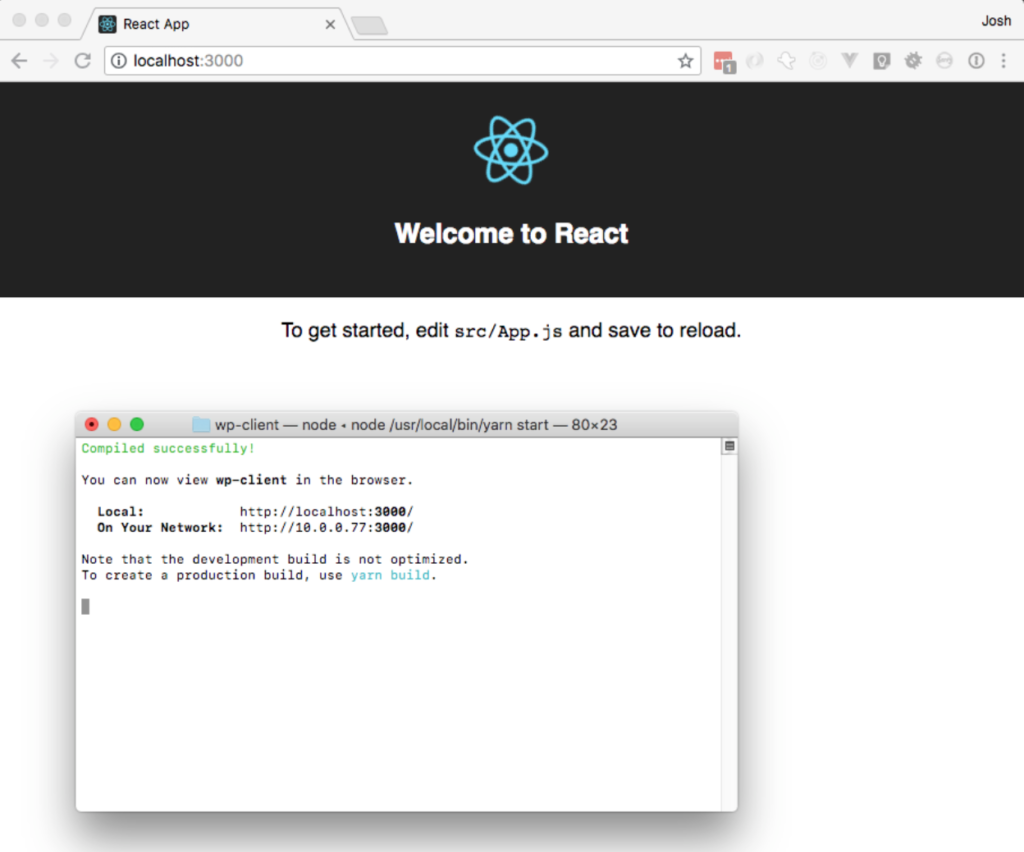

Once that’s complete, your terminal should show you the URL for your local dev server. Here is a screenshot of my terminal and browser with the default app.

By default, create-react-app adds one test. Open up another terminal, in the same directory and start the test watcher:

View the code on Gist.

The tests are being run using Jest. create-react-app assumes you have Jest installed globally. If that command does not work, do not install Jest or jest-cli into your project. Instead, install globally using npm:

View the code on Gist.

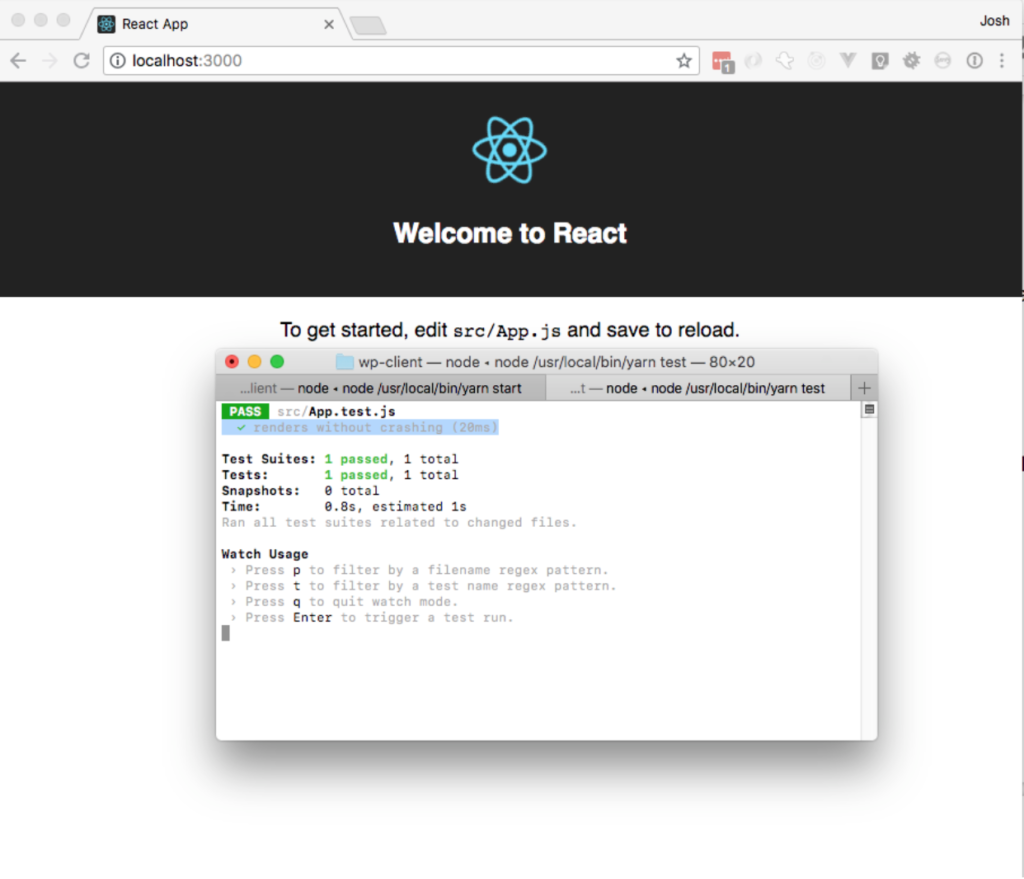

The terminal should look like this:

That’s one test, which basically covers if mounting the app causes an error or not. That’s a good catch-all acceptance test, but not the kind of isolated unit test we want and running it shows us if we have tests running or not.

Jest has a pretty simple API. Let’s look at one test suite, with one test, before jumping into something more practical.

View the code on Gist.

Test suites are defined by the function described. Everything inside of its closure is considered part of one test suite. Organizing tests into test suites makes them easier to read and you can skip a whole suite or add a specific setup or teardown function to the suite.

Inside of a test suite, we use the function it() to isolate one test. Both describe and it accepts to arguments. The first is a string describing the test suite or test, the second is a function that performs the test. Think about the metaphor this way please: “describe a group of features, it has one specific feature.”

Inside of the test, Jest gives us the expected function. We provide expect with the result of the function being tested and then make an assertion. In this case, we’re using the toEqual assertion. We are asserting that the input we expect to equal a value, does equal that value.

Since pure functions have one output and no side-effects, this is a simple way to test.

Iterate Safely

That’s the basics of Jest. With Jest, you can run basic tests as I’ve shown in this post. As this series continues, I’ll cover snapshot testing React components with Jest and the React test renderer. For more complex testing, I’ll introduce Enzyme.

Specific technologies aside, keep in mind WHY we have tested: so we can iterate on our code safely. When we make a change to our codebase to fix a bug or add a new feature, we need to know that no new bugs or other unintended side effects are introduced as well. Testing gives us that assurance. By following a test-driven approach, you can confidently add new features to components and apps, allowing for an iterative approach to application interface development.

The post Getting Started With React Unit Testing For WordPress Development appeared first on Torque.